It could be argued that the first book ever written on Taekwondo was a book published by Hwang Ki in 1958. The book is called ‘Tangsudo Textbook’ – now while it could be counter-argued that this makes it a book on Tangsudo and not Taekwondo (particularly since Hwang Ki’s Mudeok-kwan remained separate from the other kwans of the Kwan Era, and since Hwang Ki’s style of martial arts still exists today, and still uses the name Tangsudo) Mudeok-kwan was one of the nine original kwans, and this book is about the style of martial arts that were being practised in Korea at this time. The first book to be published with the name ‘Taekwondo’ on it was published by Choi Hong-hi a year later.

Hwang Ki’s book is freely available to view online. A copy of the book is owned by the University of Hawaii in Manoa, and they have scanned the book and made it available online here: http://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10524/1073

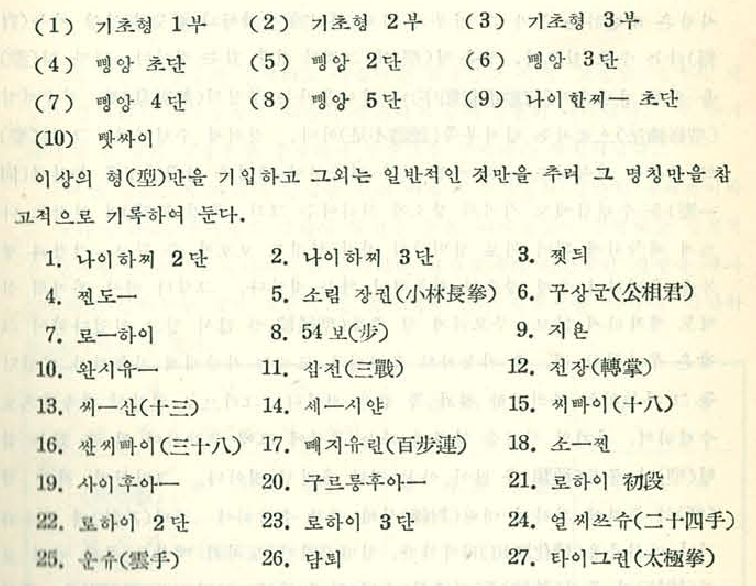

On page 19 of the book is some fascinating information. Hwang lists the forms that are practised in Tangsudo:

There are a number of things that are fascinating about this information. Firstly: the spellings of the names of these forms. Hwang lists a series of five forms that are called the 삥앙 pping-ang forms. These are clearly the Pinan forms from Karate (here Hwang uses the Okinawan name for them, rather than the Japanese, which is Heian). Unlike nowadays, when it’s relatively easy to use various dictionaries to find the correct Korean pronunciation of Japanese words, Hwang has simply best approximated the Japanese pronunciation of the name of each form using hangeul.

So in order to find out which forms Hwang is talking about here, the first thing we have to do is match each one to the correct name of the form.

Section 1:

- 기초형 1부 gicho hyeong 1 bu – This is actually the correct name of the form – 기초 gicho – a series of three basic forms still practised in some schools today.

- 기초형 2부 gicho hyeong 2 bu

- 기초형 3부 gicho hyeong 3 bu

- 삥앙 초단 pping-ang chodan – Clearly Pinan – a series of five basic forms – called Heian in Japanese Karate. The correct name for them in Korean is 평안 Pyeong-an.

- 삥앙 2단 pping-ang 2 dan

- 삥앙 3단 pping-ang 3 dan

- 삥앙 4단 pping-ang 4 dan

- 삥앙 5단 pping-ang 5 dan

- 나이한찌ー 초단 naihanjji chodan – Clearly Naihanchi – a series of three forms, of which this is the first. The series is also called Tekki in Japanese, and 철기 Cheolgi in Korean.

- 빳싸이 ppatssai – Clearly Passai – called Bassai in Japanese Karate. The correct Korean translation is 발새 Balsae.

There’s nothing all that odd about the forms in section 1. This is a fairly standard list of forms that colour belt students today practise as they progress towards black belt. What’s mainly of interest in section 1 is how Hwang has approximated the pronunciations of the names of the forms.

Section 2:

- 나이하찌 2단 naihajji 2 dan – Clearly Naihanchi Nidan – no idea why Hwang changed the spelling here from that in section 1.

- 나이하찌 3단 naihajji 3 dan

- 찟듸 jjitdui – Clearly Jitte.

- 찐도ー jjindo – Clearly Chintō.

- 소림 장권 (小林長拳) sorim janggwon – This is fascinating – more on this further down.

- 꾸상군 (公相君) kkusanggun – Clearly Kūshankū. The correct name in Korean is 공상군 Gongsanggun.

- 로ー하이 rohai – Clearly Rōhai. The correct name in Korean is 로학 Rohak.

- 54 보 (步) 54 bo – Clearly Gojūshiho. The correct name in Korean is 오십사보 Oshipsabo.

- 지욘 jiyon – Clearly Jion. The correct name in Korean is 자은 Ja-eun.

- 완시유ー wanshiyu – Clearly Wanshū. The correct name in Korean is 완수 Wansu.

- 삼전 (三戰) samjeon – Clearly Sanchin (based on the hanja).

- 전장 (轉掌) jeonjang – This is the form Tenshō. It’s not obvious from the hangeul, but the meaning of the hanja is the same as that of the kanji for Tenshō.

- 씨ー산 (十三) sshisan – Clearly Seisan.

- 세ー시얀 seshiyan – This would appear to also be Seisan. There are multiple different pronunciations of the name of the Karate form – this is probably why the form is listed here twice.

- 씨빠이 (十八) sshippai – From the hanja this is clearly Seipai.

- 싼씨빠이 (三十八) ssansshippai – It’s not obvious which form this is. The hanja means ’38’, implying that there are 38 movements in the form, but there is no Karate kata with this name. It’s possible that there is an error on this line in the book, and that this should say 三十六, which is the name of a form – Sanseirū – meaning ’36’.

- 빼지유린 (百步連) ppaejiyurin – This is interesting – this would appear to be the form Pechurin (based on the hangeul). Not much has been written about this form in English, and this is the first time I’ve seen hanja / kanji written for it anywhere. The correct hangeul writing of 百步連 is 백보련 Baekboryeon, and it roughly means ‘100 continuous steps’.

- 소ー진 sojin – Clearly Sōchin.

- 사이후아ー saihua – Clearly Saifa (there is no corresponding letter for ‘f’ in Korean, so here it’s been approximated as a ‘h’).

- 구르룽후아ー gureurunghua – It’s not obvious from the romanisation, but from the pronunciation this is clearly Kururunfa.

- 로하이 初段 rohai chodan – Clearly Rōhai. Again, Hwang has already listed this form further up. Here Hwang seems to suggest that there are three Rōhai forms, and that this is the first.

- 로하이 2단 rohai idan

- 로하이 3단 rohai samdan

- 얼 씨쓰슈 (二十四手) eol sshisseushyu – This again is interesting. There’s no Karate form with this exact name, but there is one that’s similar: 二十四歩 Nijūshiho. 二十四手 means ‘twenty-four hands’, whereas 二十四歩 means ‘twenty-four steps’. A lot of Karate forms have a name that’s a number followed by ‘hands’ or ‘steps’ so the difference isn’t significant. What’s particularly interesting here, however, is that Hwang’s phonetic approximation using hangeul is not a phonetic approximation of the Japanese pronunciation – eol sshisseushyu and nijūshiho clearly sound nothing alike. But it is a phonetic approximation of the Chinese pronunciation of 二十四手, which is èrshí

sìshǒu (in Mandarin). (If you’re not used to reading romanised hangeul or Hanyu Pinyin, then you’ll just have to trust me that the pronunciations of these words are very similar.) This shows that Hwang had a knowledge of how certain words were pronounced in Chinese. - 운슈 (雲手) unshyu – Clearly Unshu.

- 담퇴 damtoe – There is no Karate kata with a name like this.

- 타이그권 (太極拳) taigeugwon – This one’s complicated – more on this below.

There’s a lot to remark here.

Firstly is Hwang’s use of the character ー. While this character looks like the Chinese character 一 yi, meaning ‘one’, it probably isn’t. It’s quite likely a character known as a chōonpu in Japanese. In Japanese, the basic phonological unit is a mora rather than a syllable. A single syllable in Japanese can be comprised of one or two morae – a syllable with two morae has a greater stress or length than a syllable with one mora. Hwang is trying to represent the Japanese pronunciation of words using hangeul, and it seems like he’s borrowed the chōonpu character from Japanese in order to represent the stressed syllables. (Read more about this character here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ch%C5%8Donpu)

Now by far the most interesting form listed in section 2 is the one called Sorim Janggwon. This is interesting because there is no Karate kata with this name. (If there were, it’s name in Japanese would be Shōrin Chōken.) Any time the characters 小林 appear in Korean and Japanese martial arts, it’s usually a reference to the Shaolin Temple in China. Since this form has not come from Japanese Karate, the presence of this form in this list would appear to show some Chinese influence on Hwang’s style of martial arts.

This is crucial because Hwang reportedly studied martial arts under a Chinese instructor for a while, but the veracity of this is uncertain. The fact this form appears in this list may support the idea that Hwang had some training in Chinese martial arts.

The name 小林長拳 altogether means ‘Shaolin Long Fist’.

This Chinese influence may be further supported by the last two items in the list. The penultimate item is 담퇴 damtoe. There’s no Karate form with a name anything like this, so it’s nothing to do with Karate. But this sounds very strongly like Tántuǐ – from Chinese martial arts. It’s difficult to discern more about this from the information given, but you can read more about Tántuǐ here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C3%A1n_Tu%C7%90

The final item, 타이그권 (太極拳) taigeugwon, is interesting – it could be a reference to several things. There is a series of three forms in Karate called Taikyoku, which has the same kanji 太極. These forms are known to have been practised in Korea at this time, and they appear in Choi Hong-hi’s 1959 book, as well as many others. However, 太極拳 is also the name of the Chinese martial art Tàijíquán – more commonly known in English as Taichi. The fact that Hwang has given the full name of that martial art style here, rather than just the name for the Karate form, suggests that here he is referring to the Chinese martial arts style. Why he’s referring to this in a list of forms is not clear; however, it would further support the idea of Chinese influence on Hwang’s style of martial arts.