In 2014 I published a book titled Taekwondo Forms. The aim of the book was to document a wide variety of forms in a consistent style, making it easy to compare and reference those forms.

The book covers most of the forms from four major styles of Taekwondo. There are, however, forms from those styles and others that are not covered by the book. Among those not included is a series of forms known as the ‘Kuk Mu’ forms, which are reportedly practised by students in some Cheongdo-kwan Taekwondo schools.

The Kuk Mu forms are very obscure. Online, there are only a few references to these forms – there are a few websites listing the movements of the forms in English, and there are a few videos on YouTube showing the forms. In printed materials, I have so far only found two references to the forms. Importantly, one of them is Son Deok-seong’s book: Korean Karate. Son Deok-seong was the successor to Li Won-guk, who established Cheongdo-kwan. Son Deok-seong’s books are therefore quite significant in Cheongdo-kwan Taekwondo, and the appearance of the Kuk Mu forms in Korean Karate confirms that they are part of the Cheongdo-kwan style (even if they are not practised by or known to a large number of students in that style).

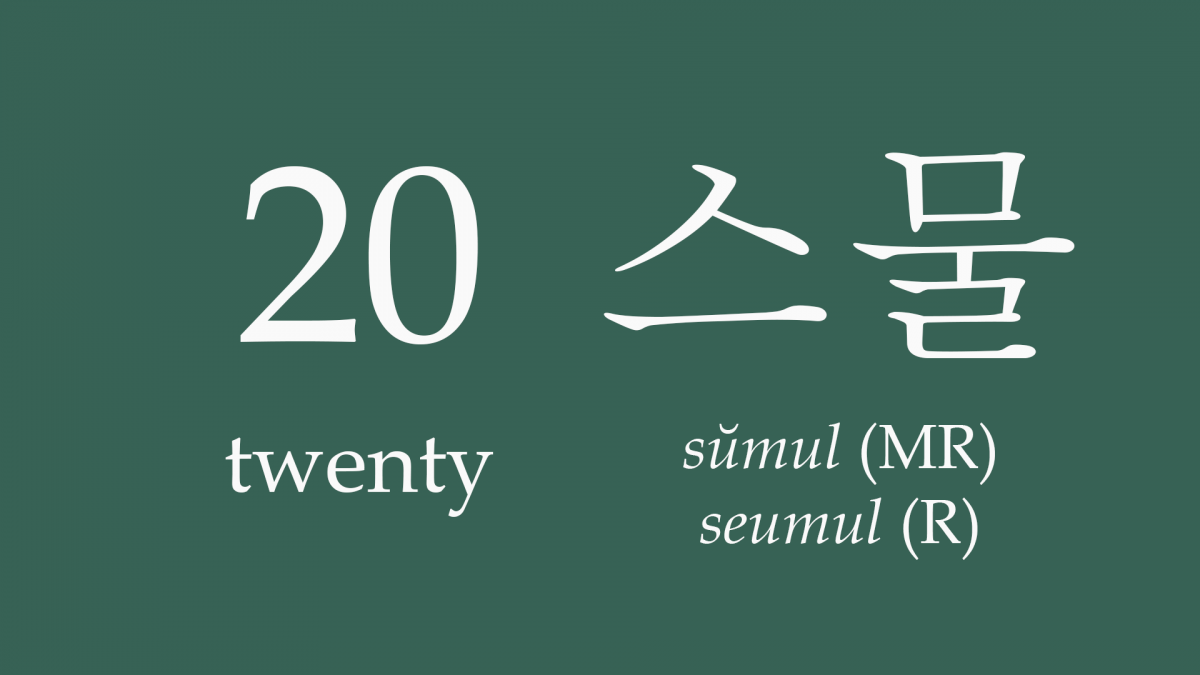

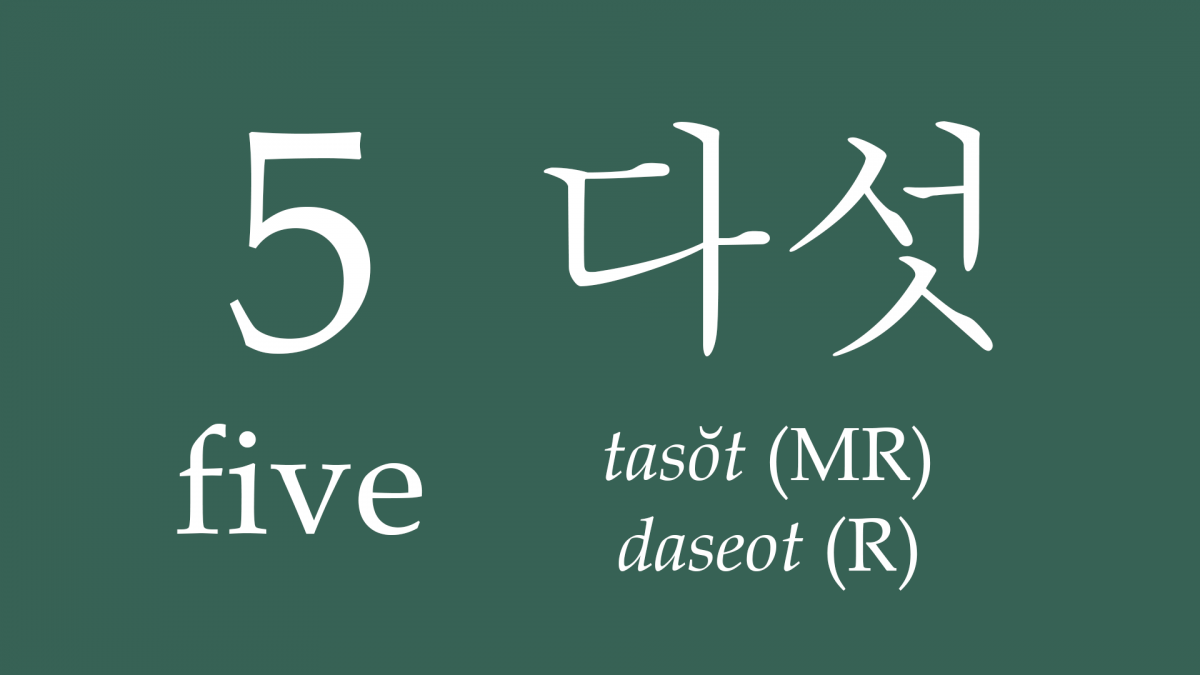

The hangeul for Korean terms is rarely given online, and even in textbooks on Taekwondo it is unusual to see, and the hangeul or hanja for ‘Kuk Mu’ are not given in Son’s book. In Korean Karate, however, and in many places online, the meaning of the name ‘Kuk Mu’ is said to be ‘national art’. This means that the first syllable is 국 國 guk – meaning ‘country’, ‘land’, or ‘nation’ – and the second syllable is 무 武 mu – meaning ‘war’ or ‘martial art’ (which is also the bu from 武道 budō, and the wu from 武术 wǔshù). Because of the pronunciation changes that take place in Korean, these two syllables together should be romanised (and pronounced) gungmu (in the Revised Romanisation of Korean). This is the correct writing of the name of the form, and is what I will use everywhere else in blog posts and books that I write. (Though perhaps the most helpful spelling of the name is kungmu (the spelling in the McCune-Reischauer Romanisation), which will most closely approximate the pronunciation for non-hangeul readers.)

Most descriptions of this series of forms agree that there are five forms in the series. In Korean Karate, only two Gungmu forms are listed, but Korean Karate specifically does not list all of the forms practised in Cheongdo-kwan – higher level forms in particular are omitted from the first book. Some higher forms are listed in Black Belt Korean Karate, but only four, and none of them are Gungmu forms. Given that black belts normally have more than four forms to practise, it seems likely that there are more forms that were not added to Black Belt Korean Karate either.

Beyond that, most video sources and written descriptions seem to agree on what the movements of these forms are – this could be because of a limited number of practitioners in Cheongdo-kwan, and so a limited potential for variation.

The Gungmu forms need to be written about and analysed more. They are only described in a few places, and many of those descriptions are idiosyncratic, and not detailed enough.

A list of websites that give information on the Gungmu forms

(I would not consider all of these to be reliable and authoritative – some of them are and some of them aren’t)

- http://www.martialtalk.com/threads/classic-tkd-forms.69720/

- https://sites.google.com/site/cdktkd/forms

- https://sites.google.com/site/sdkoreankarateclub/forms/kuk-mu-1

- http://www.kidokwan.org/about/korean-martial-art-kwans/chung-do-kwan-%EC%B2%AD%EB%8F%84%EA%B4%80-%E9%9D%91%E6%BF%A4%E9%A4%A8/chung-do-kwan-forms/

- http://bluewavestl.com/forms-videos/

- http://livingstonkarate.com/training-aides/formskata/kuk-mu-1/

- https://www.taekwondoforums.com/threads/chung-do-kwan-patterns.897/