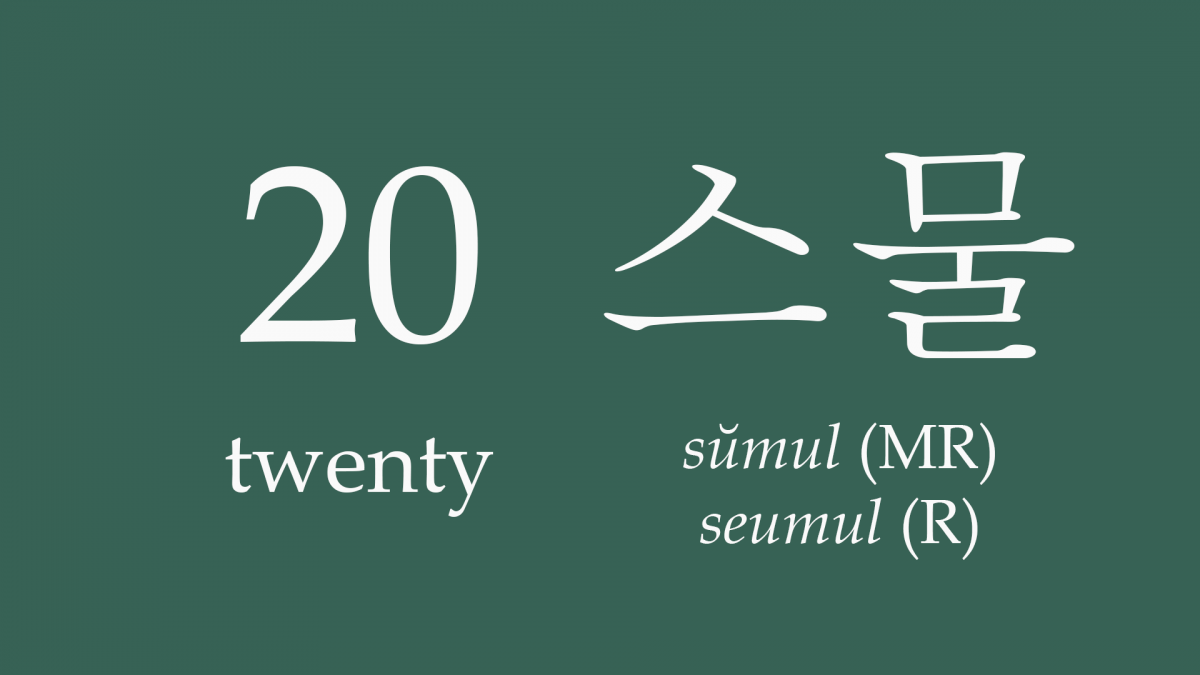

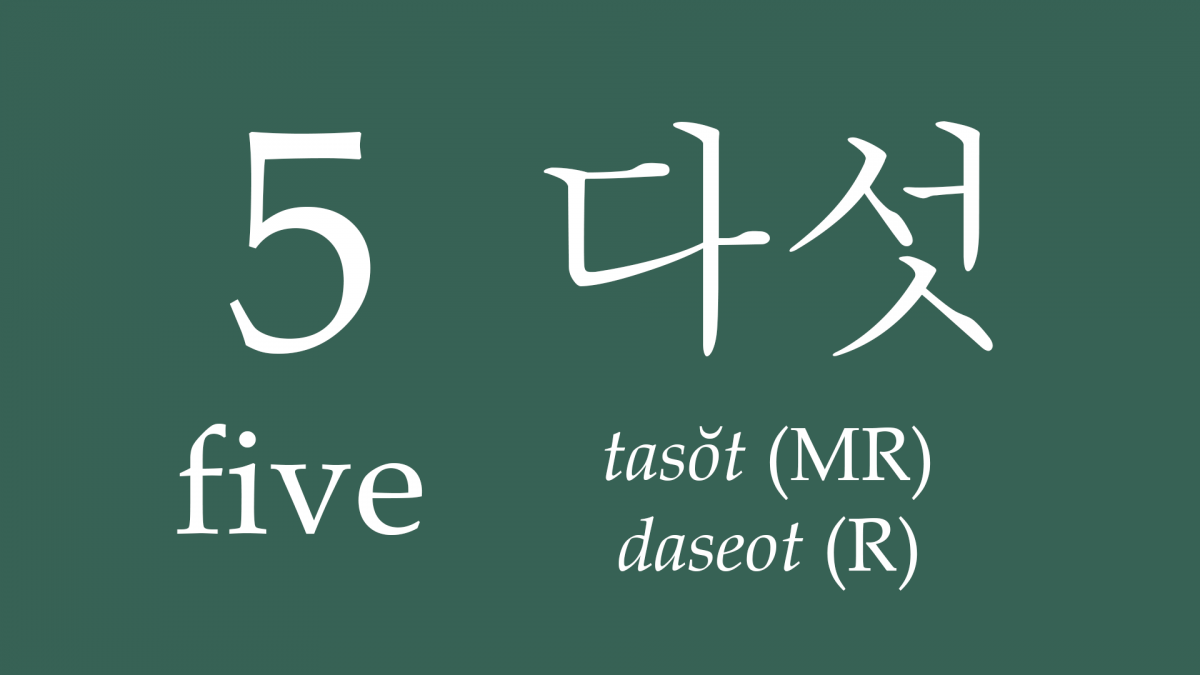

In this third video in the series on counting in Korean, we look at how to count from 1 to 10 in Sino-Korean numerals.

Tag: Korean

How to count from 10 to 100 in Korean – Taekwondo Terminology Tutorials

The second video in the series – in this video we look at how to count from 10 to 100 using native Korean numerals.

First Video! How to count to 10 in Korean – Taekwondo Terminology Tutorials

What is hopefully the first of many videos, in this video we look at how to count to ten in native Korean numerals.

New Kukki-won forms: a break from tradition?

What is a form? In a literal sense, it is a sequence of movements designed to be instructive or useful in some aspect of Taekwondo training. Forms have many uses. They teach correct stances and stepping, posture and balance, timing. Most importantly they teach you the basic form of each movement: how to punch in an offensive stance, how to maintain a defensive stance.

But there are some exercises in Taekwondo which also have all of these attributes, but which are not considered forms. Set sparring would be an example of this. (There is a broader point here as to whether a set sparring exercise could be considered a form, but that’s a topic for another post.) However, there are some differences between set sparring and forms that would allow us to define what a form is more narrowly. Set sparring is generally practised with an opponent; forms are an individual activity. A form could be defined as an instructive sequence of movements that is performed by one person. But then, in Changheon-yu Taekwondo, there is the exercise called 사주 지르기 Saju Jireugi, which also fits this definition but which is universally not considered a form (sometimes to the confusion of white belt students).

All of these considerations lead to a new question: what is the defining quality of a form? What is it that makes a form a form?

Returning to the example of Saju Jireugi in Changheon-yu Taekwondo, the explanation that’s often given for why this exercise is not a ‘form’ is that it doesn’t have an interpretation. The other such exercises in Changheon-yu Taekwondo – 천지 Cheonji, 단군 Dan-gun, 도산 Dosan, and so on – all have lengthy explanations of what the name means, given by Choi in his encyclopaedia. Saju Jireugi does not have a lengthy interpretation, just a short literal translation of ‘punching in four directions’ or more commonly ‘four-directional punch’. I find this distinction arbitrary – Saju Jireugi does have an interpretation, just a short one instead of a long one. A translation is a kind of interpretation.

Saju Jireugi is ultimately very similar to the exercises above it. In fact the only real differences seem to be that it’s easier than all of the other exercises in Changheon-yu (though it’s only slightly easier than Cheonji), and that the name of the exercise has no 한자 hanja writing (지르기 jireugi only has a 한글 han-geul writing). And in fact I think this second difference is quite significant.

All of the other twenty-five forms in Changheon-yu (including both 고당 Kodang and 주체 Juche) are consistent in how they’re named. They’re all named after a person, a group of people, a place, or a philosophical concept. They all have a writing in both han-geul and hanja. And they are all exactly two syllables long. This last part perhaps reveals Choi’s intentions. There are many examples of when Choi takes a longer name or word, and shortens it for the name of a form: 연개소문 Yeon Gaesomun was shortened to 연개 Yeon-gae, 을지문덕 Eulji Mundeok was shortened to 을지 Eulji, and there are several other examples.

I think the fact that Choi chose to give the other exercises, the forms, in Changheon-yu, names that fitted these criteria, and that he did not give Saju Jireugi such a name, is what means that Saju Jireugi is not a form.

Now at this point, I would expect the reader to point out that the conventions that apply to Changheon-yu don’t necessarily apply to other styles of Taekwondo. That’s true. However, when looking at the forms that are practised in other styles of Taekwondo, it is apparent that these conventions on form names are broadly true of Taekwondo in general.

These conventions are followed for many of the forms that have been inherited from Karate. (Now, this is arguably not a valid example. Forms loaned from Karate are arguably not ‘Taekwondo’ forms, since they were not designed or named by someone who practises Taekwondo. Also, since they were not named by Taekwondo practitioners, they are arguably not relevant when discussing the naming conventions of forms in Taekwondo. However, the style of the names of Karate 型 kata almost certainly inspired the way in which Taekwondo 형 hyeong are named, and their similarity supports this idea.) 平安 Heian, 披塞 Bassai, 燕飛 Enpi, 明鏡 Meikyō, 観空 Kankū, 鉄騎 Tekki, 十手 Jitte, 半月 Hangetsu, 慈恩 Jion, and more all follow this pattern. (Hangetsu is three syllables but it’s only two 漢字 kanji characters.) In this list I have included many kata that were renamed by 船越 義珍 Funakoshi Gichin, the founder of 松濤館 空手 Shōtō-kan Karate, whom many of the early practitioners of Taekwondo are believed to have been taught by. Many of these kata appear in early editions of Choi’s encyclopaedia, as well as Hwang Ki’s textbooks, indicating that these kata, as well as Funakoshi, had an influence on the idea of what a form is, and how a form should be named, in Taekwondo.

And in Kukki-won Taekwondo, these naming conventions have been followed up until this point: 팔괘 八卦 Palgwae, 태극 太極 Taegeuk, 고려 高麗 Koryeo, 금강 金剛 Keumgang, 태백 太白 Taebaek, 평원 平原 Pyeong-won, 십진 十進 Shipjin, 지태 地跆 Jitae, 천권 天拳 Cheon-gwon, 한수 漢水 Hansu, and 일여 一如 Iryeo all follow this pattern.

In fact the only examples I can think of where this convention isn’t followed are in some of the forms that have been inherited from Karate, as well as the very obscure and very undocumented forms practised in early Changmu-kwan and Kangdeok-won. Several of the ten new Kukki-won forms depart from these conventions: most of them do not have hanja writings – they are based on native Korean words – and several have names with more than two syllables. The decision by Kukki-won to give new forms names that don’t follow these conventions is a notable break from tradition.

The spellings and pronunciations of the new Kukki-won forms

Last year, Kukki-won announced that ten new forms had been developed for competitions, with many of the forms being specific to certain age ranges of the competitors.

Kukki-won has given the names of these forms in romanised forms according to the Revised Romanisation of Korean, but the Revised Romanisation is often confusing, so in order to prevent confusion on how to pronounce the names of these forms, here are the names of the ten new forms in various systems of romanisation, as well as an intuitive spelling for those generally unfamiliar with Korean.

| Han-geul | Hanja | Revised Romanisation | McCune-Reischauer Romanisation | Approximate Pronunciation | Meaning |

| 힘차리 | none | himchari | himch’ari | heem-cha-ree | ‘powerful challenge’ |

| 야망 | 野望 | yamang | yamang | ya-mang | ‘ambition’, ‘aspiration’ |

| 새별 | none | saebyeol | saebyŏl | sey-byol | ‘new star’ |

| 나르샤 | none | nareusya | narŭsya | nar-shya, nar-sha, na-ru-shya, na-ru-sha | ‘flying up’ |

| 비각 | 飛脚 * | bigak | pigak | bee-gak, pee-gak | ‘flying kick’ |

| 어울림 | none | eoullim | ŏullim | oh-oo-leem | ‘harmony’, ‘society’, ‘appropriateness’ |

| 새아라 | none | saeara | saeara | sey-a-ra | ‘sun rising sea’ |

| 한솔 | none | hansol | hansol | han-sorl | ‘great pine tree’, ‘large pine tree’ |

| 나래 | none | narae | narae | na-rey | ‘wing’, ‘bird’s wing’ |

| 온누리 | none | onnuri | onnuri | on-noo-ree | ‘whole world’ |

* This is assumed to be the hanja for the name of this form, but may not be.

Already interesting with the names of these new forms is that most of them do not have a hanja writing. This is very unusual for form names in Taekwondo; by far the majority of all forms in Taekwondo have names that can be written in both han-geul and hanja – indeed all of the other forms in Kukki-won Taekwondo have this property.

The Korean term for ‘floor diagram’

It’s very common to hear in Taekwondo classes ‘What is “walking stance” in Korean?’ or ‘What is “knife-hand strike” in Korean’. There are a large number of Korean terms that are known to most of those who practise Taekwondo. More obscure terms – for less common techniques, or philosophical concepts, perhaps – can be found in forms textbooks and similar. However, the Korean term for the floor diagram of a form is not something I see very often at all, so what should it be?

In Karate, the term for ‘floor diagram’ is 演武線 embusen. This is pronounced 연무선 yeonmuseon in Korean, and literally means ‘lines of attack’. However, with the de-japonification (can any etymologists tell me if that word is right?) of Taekwondo, this may not be the right term.

An alternative term could be 방향 표 方向 表 banghyang pyo, which literally means ‘direction diagram’. This is not a purely Korean term – it has a hanja writing – but it’s not a term that’s been borrowed from Karate.

Yeonmuseon is my preferred term. It’s what I use in all of my writings, as well as on here.

Floor diagrams statistics

What a delightfully dry topic this is.

In Taekwondo, every form has a floor diagram. The floor diagram shows the lines along which a student should move as they perform the form.

In Karate, floor diagrams, which are called 演武線 embusen, ‘lines of attack’, are often more literal. If you take more steps in one direction than another, this is shown on the diagram. In Taekwondo, floor diagrams, which could be called 연무선 yeonmuseon – the Korean pronunciation of 演武線 embusen – are more symbolic. The asymmetries of the form are often not shown – for example, in the Changheon-yu form Dan-gun, you start by taking two steps to the left, and then turn and take two steps to the right. The result of this is actually that you move twice as far from your starting position to the left than you do to the right, but this is generally not shown in the floor diagram.

This symbolic aspect of floor diagrams in Taekwondo is taken even further, and floor diagrams are often based on a 한자 漢字 Hanja character (indeed, the Hanja character for the form is chosen first, and then the form is designed around it). This is, arguably, one of the defining aspects of a form in Taekwondo. It’s more common in Kukki-won and Jukam-yu Taekwondo than it is in Changheon-yu.

Some Hanja characters are more popular for form design than others. In the table below I’ve counted how many forms use which Hanja character, and given the meaning and pronunciation of each character. (For this list I’ve looked at the forms that I included in my book, Taekwondo Forms, as well as a few others.) In this table I’ve included not only those forms for which the symbolism of the floor diagram is intentional, but also those for which it is co-incidental, for comparison.

(There are some forms which have floor diagrams that do not match any Hanja character – the form Dosan being the most well-known example.)

| Hanja Character | Mandarin Pronunciation | Korean Pronunciation | Meaning | Where the symbolism is intentional | Where the symbolism is co-incidental | Number of forms |

| 下 [2] | xià | 하 ha | below | Cheon-gwon | Godang, Palgwae Chil Jang | 3 |

| 上 [2] | shàng | 상 sang | above | Jitae | Pyeong-an Samdan, Pyeong-an Odan, Balsae, Yeonbi, Chungjang | 6 |

| 士 | shì | 사 sa | scholar, gentleman | Yulgok, Toigye, Koryeo | Pyeong-an Sadan, Palgwae Pal Jang | 5 |

| 工 | gōng | 공 gong | work | Taebaek | Gwan-gong, Ja-eun, Dan-gun (Choi), Wonhyo, Junggeun, Hwarang, Chungmu, Dan-gun (Bak), Palgwae Il Jang, Palgwae I Jang, Palgwae Sam Jang, Palgwae Sa Jang | 13 |

| 一 | yī | 일 il | one | Pyeong-won | Cheolgi Chodan, Cheolgi Idan, Cheolgi Samdan, Po-eun [3] | 5 |

| 十 | shí | 십 ship | ten | Shipjin | Shipsu [3], Banwol, Cheonji, Samil, Choiyeong, Yeon-gae, Munmu, Seosan, Jisang, Jigu | 11 |

| 土 | tǔ | 토 to | land, territory | Gwanggae | 1 | |

| 山 | shān | 산 san | mountain | Juche, Keumgang | 2 | |

| 乙 [1] | yǐ | 을 eul | second | Eulji | 1 | |

| 王 | wáng | 왕 wang | king | Sejong | Taegeuk Il Jang, Taegeuk I Jang, Taegeuk Sam Jang, Taegeuk Sa Jang, Taegeuk O Jang, Taegeuk Yuk Jang, Taegeuk Chil Jang, Taegeuk Pal Jang [4] | 9 |

| 平 [1] | píng | 평 pyeong | peace | Pyeonghwa | 1 | |

| 女 | nǚ | 여 yeo | woman | Seondeok | 1 | |

| 水 [1] | shuǐ | 수 su | water | Hansu | 1 | |

| 卍 | wàn | 만 man | a sacred and auspicious symbol in Buddhism | Iryeo | 1 | |

| None | – | – | – | – | Pyeong-an Chodan, Pyeong-an Idan, Myeonggyeong, Dosan, Gyebaek, Uiam, Yushin, Tong-il, Jugam, Palgwae O Jang, Palgwae Yuk Jang | 11 |

[1] This character is made more geometric for the floor diagram.

[2] The lateral dash is not part of the floor diagram.

[3] This may actually be intentional.

[4] The symbolism of the floor diagrams for the Kukki-won Taegeuk forms is intentional, but the floor diagram is supposed to look like a trigram, rather than the Hanja word for ‘king’.

So it seems that 工 gong is the most popular, followed by 十 ship and 王 wang (which is mainly because all of the modern Taegeuk forms have that diagram). It’s easy to see why these are the most popular – they’re quite simple, and they’re symmetric, and they allow for easy stepping between the lines of the diagram.

When I write about forms, I will often describe a form as having a ‘工 gong shaped floor diagram’, or a ‘十 ship shaped floor diagram’, even if the symbolism is not intended, because it’s quite a convenient way of showing what the diagram is.

Special doboks for referees in Taekwondo

I have always liked the dobok. Its design allows for free movement while also looking strong and powerful. It is traditional, and a symbol of Korean culture, but not inconvenient or uncomfortable.

Two or three times a year I go to officiate at Taekwondo competitions, and have been doing so for about eight years. For the competitions, officials are instructed to wear black trousers, and a black v-neck t-shirt with the word ‘Official’ embroidered onto it – we’re given the t-shirt when we first go to officiate at a competition. Most people generally wear sports shoes.

I think that the monotonous and undistinctive clothing that the officials wear does not help to give the sense of authority and expertise that we need. The officials are ultimately the people running the competition, and that involves doing things like keeping the audience from intruding on the rounds, telling competitors where to go and more generally what to do, and even disqualifying competitors if they break the rules of the competition. The officials are also expected to know a lot about Taekwondo – both the art itself and the rules of the competition. The officials need to be seen as authorities and experts, and how we look can influence that.

As such, I have long thought that officials in Taekwondo need a special design of dobok to wear at competitions. Being a dobok, officials could wear their belts with it, which would remind everyone that these officials ARE black belts, and they are very skilled in Taekwondo themselves – they’re not just people who’ve been taught the rules and brought in to help. Having a different design – i.e., one that’s not white – rather than just wearing the existing black belt doboks, would make it easy to tell the officials and the competitors apart – which is vital during rounds – otherwise the competitors would mistake the referees for their opponents and start fighting them. Having an exclusive design would also add to the sense of authority that the officials have.

Having special clothing for referees would not be unique to Taekwondo – referees in Sumō have their own styles of clothing – indeed refereeing in Sumō is seen as an art as much as the wrestling itself is, and Sumō referees have their own traditions. And in Taekkyeon – one of the ancestors of Taekwondo – they have special referees’ doboks. In Taekkyeon they are bright yellow – perhaps not a good choice of colour for Taekwondo, but if Taekkyeon can have special referees’ doboks, then we in Taekwondo definitely can too.

So what should the design be? Well, the normal dobok is white, and black belts get some black edging to it. In the organisation that I train with, instructors have a black dobok, which has gold lettering embroidered onto it. It has always seemed slightly odd to me to give instructors a black dobok, since black is the colour of expertise or perfection in Taekwondo, but masters’ doboks are still white. Nevertheless, the referees’ dobok could also be black, symbolising a different kind of expertise to that of the instructors. The instructor is skilled in teaching; the referee is skilled in scoring a fight.

But to avoid the symbolism of black, the referees’ dobok could be dark blue or dark red. Blue and red are the colours of the Taegeuk, as seen on the flag of South Korea. If the doboks had gold embroidery, they would not look dissimilar to the clothing worn by the aristocracy of ancient Korea. Yellow also has traditional symbolism – it is one of the colours of the Samsaeg-ui Taegeuk – perhaps appropriate as it’s the colour that represents humankind (blue and red represent the sky and the earth). However, yellow is bright and garish, so likely to be unpopular. Orange, magenta, and purple are also too garish. Green has no particular symbolism, and is an odd colour choice for a dobok generally. Brown and grey are too dull.

So blue, red, or yellow would all be advisable colours, with gold embroidery. No black edging – I think that would be too much. Despite the challenge of designing and manufacturing a dobok, and then persuading practitioners to buy it and wear it, I think having special doboks for referees would be worth it.

How to spell ‘Taekwondo’

From the title of this post, and indeed the title of this blog, you can already see what my opinion on this is. Let me explain it.

I see ‘Taekwondo’ written in a lot of different ways. I see it written: Tae Kwon Do, Tae Kwon-Do, Tae-Kwon-Do, TaeKwon-Do, TaeKwon-do, Taekwon-Do, Taekwon-do, TaeKwonDo, TaeKwondo, Taekwondo, taekwondo, T’aegwŏndo, Taegwondo. (All of these different ways written deliberately and not mistakenly.)

Most of these writings vary only in whether syllables are separated by spaces and hyphens, and in capitalisation.

I think that the correct way to write 태권도 is ‘Taekwondo’. No spaces, no hyphens, no capital letters in the middle of the word, but the first letter should be a capital letter.

Firstly, why shouldn’t there be any spaces? ‘Taekwondo’ is one word in Korean. It would be like, in English, instead of writing ‘information’, writing ‘in form ation’. Certainly, each of the syllables in ‘Taekwondo’ has meaning – just as ‘in’, ‘form’, and ‘ation’ have distinct etymological meanings – and looking at the separate meanings is how we learn what the whole word means, but ‘Taekwondo’ is not three words, it is one.

Why shouldn’t there be any hyphens? In large part for the same reason that there shouldn’t be any spaces. Writing ‘Tae-Kwon-Do’ suggests that it’s three words rather than one. Writing ‘Taekwon-do’ suggests that the ‘do’ is a suffix that can be omitted as with ‘Karate-do’, but no-one ever calls ‘Taekwondo’ just ‘Taekwon’.

Furthermore, in the McCune-Reischauer and Revised systems of romanisation, hyphens are significant. They are used to separate letters that English speakers may interpret as a single sound – specifically they are used to distinguish between ‘ng’ and ‘n-g’. An example of this is in the word 평안 pyeong-an. If the hyphen were omitted from the romanisation, this would be written ‘pyeongan’, but this is ambiguous – is the pronunciation like ‘pyeong-an’ or ‘pyeon-gan’? Thus, hyphens shouldn’t be used to separate syllables unless necessary to help with pronunciation.

Why shouldn’t there be any capital letters WITHIN the word, like in ‘TaeKwonDo’? This is just bad English. The trend for using capital letters in the middle of words (like in ‘YouTube’) is a modern phenomenon that’s used most often in brand names. It’s inelegant, and looks very odd if you dO iT aLl ThE tImE.

Why should there be a ‘k’ instead of a ‘g’? G’s in Korean words tend to be confusing. For example, the romanisation of 고려 according to the Revised Romanisation is goryeo, but the ㄱ in this position is pronounced more like a ‘k’ than a ‘g’, which is why writing this word as ‘koryo’ makes a lot of sense. This is also true of a word like 국기원 – written gukgiwon in RR, but more familiar when written kukkiwon. When the ㄱ is in the middle of the word, the pronunciation IS often more like a ‘g’, but a ‘g’ is often still confusing for English speakers, so a ‘k’ should be used. (Similarly, I advocate writing ‘kukki-won’ rather than ‘gukgiwon’, ‘songdo-kwan’ rather than ‘songdogwan’, and so on.)

And finally, why should ‘Taekwondo’ always start with a capital letter? ‘Taekwondo’ is a proper noun – it is a name – not capitalising the first letter would be like writing ‘britain’ or ‘korea’. Taekwondo is a specific style of martial arts, much the same way that Impressionism is a specific style of western art, and both should be written with a capital letter at the start.

My conventions when writing Korean text

I write a lot about Taekwondo. At the time I’m writing this blog post, I have written nine books on the subject. I write a lot about the terminology used in Taekwondo, even if that’s not the main subject of the book or post. If I use a Korean word in the text, I will give the han-geul, hanja, and romanisation for the word in-line. I do this because a lot of authors mis-romanise Korean words, sometimes to the extent where you can’t be sure what word they mean. Korean is the proper language of Taekwondo, even though probably more of the art’s practitioners are not Korean and do not speak conversational Korean. When authors mis-romanise han-geul, the reader can’t be sure what the correct Korean is, and what the correct pronunciation is, and this leads to a degradation of knowledge among Taekwondo practitioners. By including the han-geul directly in the text, the reader never has to look it up, and can be sure that the romanisation presented is correct.

However, adding the han-geul, hanja, romanisation, and translation for most of the terms I use into the text is quite difficult to do right – it’s a lot of information and if it’s not presented well and consistently, then it’s confusing. Here are the conventions I use for adding Korean into what I write, and why I use them.

Let’s say I want to put the word dojang into a sentence. I put the han-geul, 도장, first, because Korean is the proper language of Taekwondo, and so should come before anything else. If the han-geul has a writing in hanja, which for dojang is 道場, that will come immediately after the han-geul, separated by a space. I think it’s important to write the hanja because if it’s not there then the reader may have to look it up, which is time-consuming and not straight-forward for the average reader. After that I will write the romanisation. I use the Revised Romanisation of Korean. The main reason I use this romanisation system is because it’s what I’ve always used, and I want to be consistent with what I’ve already written. I actually think that the McCune-Reischauer system is better at representing the pronunciation of Korean. I will sometimes include the McCune-Reischauer Romanisation of the word in parentheses () if I think it’s useful. The romanisation I always put in italic text – which is why I always put Taekwondo in italics.

So for dojang, I would normally write this in the text as: 도장 道場 dojang

If I’ve already written the han-geul and hanja for a word in the book or post that I’m writing, I won’t include it a second time if I write the word again (the exception being for lists of movements of forms).

These conventions give the reader a lot of information, make it very easy for the reader to find out the han-geul for a given word, make it easier for people whose first language is not English to interpret what I write, and reinforce Korean as the proper language of Taekwondo.